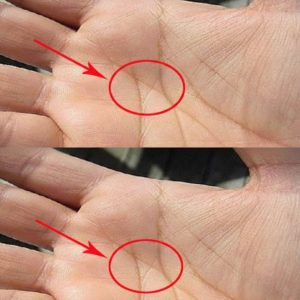

At first glance, it looks like the kind of image you’d casually scroll past — a neat stack of geometric blocks arranged in a clean pattern, paired with a bold caption daring you to participate. It feels harmless. Almost trivial. A quick brain teaser designed for a few seconds of attention before moving on. The instruction is simple: count the squares. You glance at it, mentally tally a number, and assume you’re done. But if you pause — really pause — and attempt to count carefully, the experience changes. The task begins to feel unexpectedly slippery. The number you first felt confident about starts to wobble. New shapes appear. Previously ignored corners suddenly look important. What seemed obvious becomes ambiguous. The puzzle quietly transforms from a casual distraction into something more reflective — a small test of perception, patience, and how your mind defines “obvious.”

The mechanics behind these puzzles are deceptively simple. Most versions feature stacked squares arranged in flat or pseudo-3D structures. Some faces are fully visible; others are partially obscured by overlap or perspective. There is no advanced arithmetic involved. The challenge lies entirely in visual interpretation. Human perception is not a perfect recording device. The brain filters information constantly, highlighting what appears most relevant and discarding what seems secondary. This efficiency allows us to navigate a complex world quickly, but it also means we often overlook subtle details. When confronted with a “count the squares” puzzle, most people instinctively count only the most prominent shapes — typically the top-facing ones. That feels sufficient. Others expand their scope slightly, including visible side faces. A smaller group becomes methodical, examining overlaps, partial squares, and implied structures. The puzzle exposes how differently people define the same task.

What makes the situation more interesting is that each approach can produce a different answer — and each answer can be internally logical. One person might interpret the instruction as “count only the squares you clearly see.” Another might assume it means “count every visible square face from any angle.” A third might mentally reconstruct the entire three-dimensional structure and count every square that exists, visible or not. None of these interpretations is inherently wrong. The divergence arises from unspoken assumptions. Online, this often leads to heated debates. Comment sections fill with confident declarations: “It’s obviously 8.” “No, it’s 14.” “You’re overthinking it.” What begins as a visual puzzle turns into a contest of certainty. The disagreement is rarely about geometry; it’s about definitions and the human tendency to defend one’s interpretation once it feels established.

Captions that claim “Most People Get This Wrong” or suggest the puzzle reveals personality traits add another psychological layer. These statements are not scientific assessments; they are social triggers. As soon as people feel evaluated, their mindset shifts. Curiosity gives way to defensiveness. Instead of exploring alternative perspectives, many double down on their initial answer. This reaction isn’t evidence of narcissism or lack of intelligence — it’s a normal cognitive pattern. Humans naturally anchor to first impressions. Once a number feels right, confirmation bias encourages us to search for evidence that supports it and ignore conflicting details. Anchoring makes it harder to adjust our count after discovering new squares. Selective attention causes us to notice bold, obvious shapes before subtler ones. The puzzle becomes a compact demonstration of how perception and ego intertwine.

Consider a simplified example. Imagine a 3×3 stack of squares arranged in layers. If you count only the top-facing squares, you might total nine and stop there. If you include partially visible front faces, the number increases. If you imagine the complete structure, including hidden squares beneath the surface, the total changes dramatically again. Each method reflects a different definition of what qualifies as “countable.” The conflict arises because the instruction never specifies the rules. In real life, this kind of ambiguity appears everywhere — in workplace misunderstandings, political debates, and personal disagreements. Two people can interpret the same instruction differently and feel equally justified. Without clarifying terms, conversations escalate unnecessarily. The square puzzle becomes a metaphor for communication: define the problem before arguing about the solution.

There’s a reason optical puzzles spread rapidly on social media. They are quick, shareable, and subtly revealing. They exploit the brain’s preference for efficiency and simplicity. We want an immediate answer. We prefer closure over uncertainty. But these puzzles reward a slower approach — examining edges, reconsidering assumptions, and entertaining alternate viewpoints. The real takeaway isn’t the final number. It’s the process. Did you pause and reevaluate when something didn’t add up? Did you remain open when someone offered a different count? Or did you cling to your first answer out of habit? In many ways, the puzzle isn’t about squares at all. It’s about how you respond to ambiguity, complexity, and disagreement. The most important shape isn’t hidden in the diagram — it’s found in the moment you choose to look again, think deeper, and allow your perspective to expand.