Sleep is one of the most essential biological processes for human survival, influencing memory consolidation, emotional regulation, immune strength, metabolic balance, and even cardiovascular stability. Although it may appear passive from the outside, sleep is in fact a highly dynamic neurological event orchestrated by complex brain networks. Throughout the night, the brain cycles through structured phases of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, each characterized by distinct electrical patterns and physiological changes. Light sleep initiates the transition away from conscious awareness, deep slow-wave sleep supports physical restoration, and REM sleep facilitates vivid dreaming and emotional processing. Among the subtle behaviors that may accompany these stages is drooling. Often dismissed as trivial or embarrassing, drooling during sleep can actually reflect how deeply the body has relaxed. As voluntary muscle control fades and swallowing slows, saliva may escape naturally. Rather than being random, this phenomenon highlights the intricate interaction between neural regulation, muscle tone, breathing patterns, sleep depth, and posture. Examining why drooling occurs reveals how delicately coordinated the sleeping body truly is and how thoroughly it surrenders to restoration.

Saliva production continues around the clock under the control of the autonomic nervous system. During wakefulness, salivary glands secrete fluid that lubricates food, begins digestion, protects tooth enamel, and supports speech. At the same time, swallowing occurs frequently and unconsciously, clearing saliva before it accumulates. As sleep begins, however, voluntary motor control diminishes. The brain reduces its oversight of skeletal muscles, including those that keep the lips sealed and the jaw gently closed. Swallowing reflexes become less frequent, especially during deeper stages of NREM sleep. When slow-wave sleep emerges, overall muscle tone declines significantly. If the mouth falls slightly open due to relaxation, saliva can pool along the inner cheek or lower lip. With gravity’s assistance, it may then escape. This process is not a malfunction but a predictable outcome of muscular release combined with reduced conscious coordination. In many ways, it signals that the nervous system feels safe enough to relinquish alertness. Instead of maintaining constant micro-adjustments in posture and swallowing, the brain reallocates energy toward tissue repair, memory consolidation, and hormonal regulation.

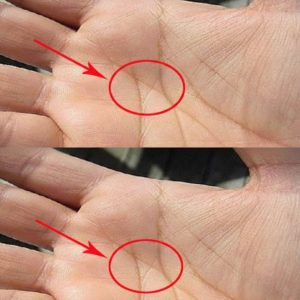

Body position plays a surprisingly influential role in whether drooling becomes noticeable. Gravity determines how fluids move, and sleep posture shapes the direction in which saliva collects. Individuals who sleep on their side or stomach are more likely to drool because saliva can gather at the lowest point of the mouth and exit more easily. By contrast, back sleeping may reduce visible drooling, though it does not alter the amount of saliva produced. Pillow height, mattress firmness, and cervical alignment further affect jaw position. If the neck tilts forward slightly or the jaw relaxes downward, the lips may part without awareness. Even minor differences in head angle can change whether saliva remains contained or escapes. These biomechanical factors explain why drooling may occur only occasionally, such as during periods of extreme fatigue, or more consistently in certain habitual positions. Importantly, posture interacts with neuromuscular relaxation rather than replacing it; drooling reflects the combined effects of muscle softness and gravitational flow. Small positional adjustments can reduce drooling, but they do not fundamentally alter the restorative nature of sleep itself.

Deep slow-wave sleep is especially relevant in understanding nighttime drooling. During this stage, brain wave activity slows into large, synchronized oscillations that indicate profound disengagement from the external environment. Blood pressure decreases, heart rate steadies, and breathing becomes more regular. Growth hormone secretion peaks, supporting muscle repair, cellular regeneration, and metabolic balance. Immune signaling molecules become more active, reinforcing the body’s defenses. Muscle tone reaches one of its lowest points of the night, allowing tissues to rest fully. As the jaw muscles soften, the mouth may drift open slightly. Because swallowing is infrequent during this stage, saliva can accumulate and escape. Paradoxically, what may appear as a minor inconvenience can coincide with optimal physical recovery. Many sleep scientists regard slow-wave sleep as the cornerstone of bodily restoration. Therefore, occasional drooling during this phase may reflect that the brain has successfully entered a deeply regenerative state. It illustrates how the relinquishing of muscular control is intertwined with healing processes that sustain long-term health.

REM sleep introduces a different but equally fascinating dynamic. In REM, the brain becomes highly active, exhibiting electrical patterns similar to wakefulness while the body remains largely immobile. This paradoxical combination supports vivid dreaming, emotional integration, and memory processing. To prevent individuals from physically acting out dreams, the brainstem induces a temporary paralysis of most voluntary muscles, a condition known as atonia. Although the diaphragm and eye muscles remain active, many facial and jaw muscles experience reduced tone. During transitions into or out of REM sleep, subtle shifts in muscle control can occur. If the mouth is slightly open and swallowing remains suppressed, saliva may leak. Because REM cycles lengthen toward morning, some individuals notice drooling more frequently in the early hours. The coordination between intense neural activity and widespread muscular inhibition underscores the complexity of sleep. Drooling can accompany these transitions, reflecting the delicate balance between brain excitation and bodily stillness. It is another example of how outward signs mirror intricate internal rhythms.

Breathing patterns further influence saliva dynamics during sleep. Nasal breathing is generally more efficient and helps maintain balanced airflow and moisture. When nasal passages are blocked by allergies, colds, or anatomical variations, mouth breathing becomes more likely. An open mouth increases the chance that saliva will gather and escape. Additionally, conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea can alter jaw position and airway stability, potentially contributing to drooling. In sleep apnea, repeated airway collapses lead to brief awakenings and fluctuating muscle tone. While drooling alone rarely signals a serious issue, persistent drooling accompanied by loud snoring, choking sensations, or excessive daytime sleepiness may justify medical evaluation. Hydration status, medications, and evening meals also subtly shape saliva production. Some medications stimulate salivary glands, whereas others suppress them, causing dryness instead of drooling. These factors demonstrate that nighttime drooling typically arises from multiple overlapping influences rather than a single cause. It reflects the broader interplay between respiratory patterns, autonomic regulation, and muscular relaxation.

Psychological state and overall health add further dimensions to this phenomenon. Chronic stress keeps the sympathetic nervous system activated, maintaining higher muscle tension even during sleep. Individuals experiencing anxiety or hyperarousal may have lighter, fragmented sleep with less pronounced muscular relaxation, potentially reducing drooling frequency. Conversely, when the parasympathetic system dominates—signaling safety and calm—digestion, salivation, and deep restorative sleep become more prominent. Drooling may therefore occur more readily during periods of emotional stability and exhaustion recovery. Age also influences patterns: infants commonly drool due to immature swallowing control, while adults typically experience it only during deep relaxation. In older adults, subtle neuromuscular changes may make it slightly more common again, though usually without pathological significance. Ultimately, drooling during sleep serves as a reminder of the body’s remarkable capacity to disengage from conscious vigilance. It symbolizes the surrender of voluntary control that allows neural circuits to recalibrate, tissues to repair, and emotions to integrate. Rather than a source of embarrassment, it can be understood as a small physiological clue that the sleeping brain and body are immersed in the quiet, intricate work of overnight recovery.