The morning light had barely begun to stretch across the horizon when 64-year-old farmer Thomas Whitaker stepped out onto his porch, pausing as he always did to take in the quiet before the day began. The rain from the night before had washed the world clean. The air smelled of wet soil and green leaves, rich and alive. His boots sank slightly into the softened earth as he walked toward the soybean fields, coffee warming his hands, hat tipped low against the rising sun.

For over forty years, Thomas had followed this same routine. Before tractors roared and engines rattled awake, before phone calls and deliveries and the steady rhythm of farm work took hold, he gave himself these moments. It was his way of listening to the land. Farming had taught him that the earth always spoke—through color, scent, moisture, and movement. You simply had to pay attention.

That morning, as he approached a shallow dip in the field where rainwater tended to gather, something unusual caught his eye. At first, he thought the early sunlight was playing tricks, reflecting off pooled water. But as he drew closer, he saw them clearly.

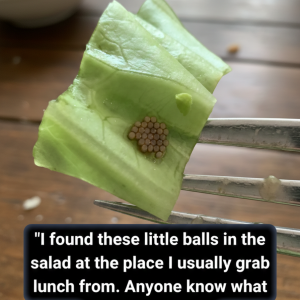

Clusters of translucent orbs rested in the mud.

They were delicate, almost luminous, each one about the size of a small marble. Dozens—maybe hundreds—were gathered together in jelly-like formations. They carried a faint bluish tint that made them look otherworldly in the golden dawn.

Thomas crouched down slowly, joints creaking in quiet protest. He had seen countless things on his land—coyote tracks, owl pellets, snake skins, even the occasional abandoned deer fawn—but this was new.

He studied the cluster carefully. The eggs were too large to belong to insects. They were too exposed and too soft for bird eggs. They didn’t resemble anything he’d encountered in decades of planting, harvesting, and walking these rows.

Thomas wasn’t a man given to panic. Farming demanded calm observation. Instead of touching them, he pulled his phone from his pocket. His granddaughter, Emma, had insisted he keep it charged and handy. “You never know what you’ll need it for, Grandpa,” she’d said.

He took several photos from different angles and stood up slowly, brushing mud from his knees.

Back at the house, he scrolled through his contacts and found an email address he hadn’t used in years. Dr. Rachel Morales.

They had met at a county fair conservation seminar nearly a decade earlier. Rachel had been fresh out of graduate school then, passionate and bright-eyed, speaking about wetland preservation and amphibian habitats. Thomas had approached her afterward, asking thoughtful questions about drainage and soil health. They had exchanged emails, occasionally sharing updates about local wildlife sightings.

Now, he attached the photos and wrote a simple message:

“Morning, Rachel. Found these in a wet patch in my north field. Ever seen anything like this?”

He didn’t expect a quick reply.

But he got one.

Within hours, Rachel responded with surprising urgency.

“Thomas, these appear to be tree frog eggs. I need to see them in person. May I come tomorrow?”

Tree frogs.

Thomas frowned. They didn’t have tree frogs in this part of the state. Not that he’d ever heard.

The next morning, a sedan rolled down the gravel road, dust rising behind it. Rachel stepped out, older now but carrying the same energy. Two colleagues followed, arms loaded with equipment.

They walked together to the field. The egg clusters had shifted slightly after another brief rain, but they remained intact.

Rachel knelt beside them, her face lighting up.

“This is remarkable,” she said. “These are consistent with Hyla chrysoscelis—Cope’s gray tree frog.”

Thomas raised an eyebrow. “Never seen one here.”

“You wouldn’t have,” she replied. “Until recently.”

The team explained that warming temperatures and changing rainfall patterns were slowly expanding the frogs’ breeding range. What had once been unsuitable farmland was becoming viable habitat during certain seasons. The shallow depression in Thomas’s field, combined with recent rains, created temporary standing water—ideal for amphibian reproduction.

“They typically lay eggs on vegetation above water,” one researcher noted. “But species adapt. These frogs may be experimenting with ground-level puddles.”

Thomas listened quietly. Climate change had always seemed distant to him—something debated on television panels and printed in headlines. But here it was, shimmering in his soil.

The researchers carefully collected minimal data but left the eggs undisturbed.

Over the following days, Thomas found himself drawn repeatedly to the puddle. Before checking equipment or inspecting crops, he visited the site.

Inside the translucent spheres, faint dark shapes began to form.

He felt a strange tenderness watching them. He had delivered calves in bitter winter storms. He had assisted hens during difficult hatchings. He understood beginnings.

But this felt different.

This wasn’t livestock. This was migration. Adaptation.

One afternoon, after studying the shallow water level, Thomas decided to act. Without consulting anyone, he brought a shovel to the area and carved a slightly deeper basin adjacent to the egg cluster. He lined it with smooth soil and allowed rainwater runoff to fill it naturally. He didn’t introduce chemicals or irrigation—just shaped the land gently.

“If you’re going to try,” he murmured to the cluster, “you might as well have a fighting chance.”

Within days, dragonflies began hovering above the water. Small birds perched nearby but kept distance. The area hummed with subtle life.

When the eggs hatched, Thomas was there.

Tiny tadpoles wriggled free, their black bodies flicking through the shallow water. The transformation fascinated him. He pulled up a folding chair and simply watched.

He began altering his field operations slightly. He marked the area with bright stakes and avoided running heavy equipment near it. It meant adjusting planting patterns and sacrificing a small strip of yield.

But it didn’t feel like a loss.

Word spread quietly. Rachel returned with her team several times. They documented the development, noting survival rates higher than expected.

“You’ve essentially created a micro-wetland,” Rachel explained.

Thomas shrugged. “Didn’t seem right to plow through it.”

By mid-summer, legs emerged from the tadpoles’ sides. Tails shortened. Tiny frogs clung to the grass along the water’s edge.

The first time he heard their chorus at dusk, it startled him. A rhythmic trill carried across the soybean rows.

He stood in the fading light, listening.

The farm had always been alive—wind in the leaves, insects buzzing, tractors humming—but this was new music.

Emma visited in late July. Thomas led her carefully to the pond.

“They’re yours, Grandpa,” she whispered, spotting a small gray frog clinging to a blade of grass.

He chuckled. “No, sweetheart. They belong here.”

Rachel’s team later confirmed that this was the first documented breeding site of the species in that county.

Local conservation groups reached out. Some asked if Thomas would consider designating a small protected wetland area permanently. He thought about it for weeks.

Farming was his livelihood. Every acre mattered. But so did legacy.

In early autumn, he agreed to set aside a half-acre buffer zone around the pond. The decision meant slight financial adjustment but offered long-term ecological stability.

The researchers installed discreet monitoring tools. They found that the frogs not only survived but returned the following spring.

Thomas found that his perspective had shifted.

He still rose before dawn. Still walked his fields. Still worried about rainfall totals and soybean prices. But now he noticed subtler things—the pattern of insects, the moisture content in shaded areas, the way birds congregated near the pond.

He had always been a steward of the land. Now he felt like a partner in its adaptation.

The frogs became a symbol—not of alarm, but of resilience.

One evening, Rachel stood beside him as the frogs called from the grasses.

“Climate change often feels overwhelming,” she said. “But this—this is adaptation in real time.”

Thomas nodded slowly.

“I’ve always known the land changes,” he replied. “Just didn’t realize I’d get to watch it decide how.”

As years passed, the pond became a permanent feature. Soybeans still grew tall around it. Harvests continued. But at the field’s edge, life pulsed in a different rhythm.

School groups occasionally visited. Thomas, once reluctant to speak publicly, found himself explaining how he had simply paid attention.

“You don’t have to be a scientist,” he would say. “You just have to notice when something’s different—and decide whether to crush it or give it room.”

The frogs multiplied. Other species appeared—salamanders, beneficial insects, migratory birds stopping briefly during seasonal shifts.

What began as glowing eggs in the mud became a living network.

On his seventieth birthday, Emma gifted him a framed photograph of the original egg cluster.

“You saw what others might have missed,” she wrote beneath it.

Thomas kept it above his desk.

Sometimes, at sunset, he stood by the pond, hands resting on the fence post. The frogs’ chorus would rise as the sky deepened into purple and orange.

The farm remained what it had always been—hard work, uncertain weather, early mornings. But it had also become something more.

A place where adaptation was visible.

A place where one decision—to observe rather than ignore—shifted the trajectory of a small ecosystem.

Thomas never sought recognition. He never considered himself extraordinary.

He had simply found something strange in his field.

And instead of plowing forward, he paused.

In that pause, life took root.

And long after the soybeans were harvested each year, long after the tractors were parked and the tools cleaned, the frogs sang on—living proof that sometimes the most profound change begins quietly, in the mud beneath your boots, when you choose to listen.