You’d be forgiven for assuming that landing the Super Bowl halftime show would come with a gigantic paycheck. After all, it’s one of the most watched live broadcasts on the planet, a cultural moment that can define an artist’s career. Yet despite the scale and prestige, performers at the Super Bowl halftime show don’t actually get paid a traditional fee. Whether it’s Rihanna, Kendrick Lamar, or 2026 headliner Bad Bunny, the rule is the same: the NFL does not cut a cheque for the performance itself. At first glance, that sounds almost unbelievable, even unfair. But the logic behind it reveals how the halftime show operates less like a concert gig and more like a once-in-a-lifetime global marketing platform. The league views the performance as mutually beneficial promotion rather than contracted entertainment, offering artists access to an audience that dwarfs even the biggest world tours. In return, the NFL maintains control over the event while keeping the halftime show framed as a celebration of culture rather than a paid endorsement. It’s a unique arrangement that has become tradition, and one that artists continue to accept because the long-term rewards often far outweigh an upfront payment.

While artists don’t receive a salary, they also aren’t expected to bankroll the spectacle themselves. According to reports cited by NME, the NFL covers all core production and travel costs associated with the halftime show. That means performers like Bad Bunny aren’t personally paying for elaborate sets, massive dance troupes, lighting rigs, or pyrotechnics worthy of a stadium audience. Instead, those costs are absorbed by the league and its commercial partners. This is where Apple Music enters the picture. As the official sponsor of the Super Bowl halftime show, Apple Music reportedly pays the NFL around $50 million annually for naming rights and branding. From that deal, artists are typically allocated a production budget estimated at roughly $15 million. That money goes toward everything viewers see on screen: stage design, costumes, dancers, musicians, security, rehearsals, and the armies of technicians and part-time workers needed to pull off a flawless live performance. What it doesn’t include, however, is a personal appearance fee for the artist. In essence, the performer receives a world-class show built around their music, image, and message—but no direct payment for stepping on stage.

For many artists, though, the Super Bowl halftime show has never been about the money. The true currency is exposure, and in this rare case, “exposure” genuinely means something. Last year’s halftime performance by Kendrick Lamar drew an estimated 133.5 million viewers, making it the most-watched halftime show in history. That level of visibility is almost impossible to buy, even for the biggest stars in music. The impact is often immediate and measurable. In the days following Lamar’s performance, his streaming numbers surged across platforms, and similar effects were already being seen with Bad Bunny even before he stepped onto the Super Bowl stage. Data from analytics firm Sudoku Bliss showed that searches for “Bad Bunny tour” jumped by more than 1,500 percent in the 24 hours after his Grammy wins, with interest still up hundreds of percent compared to the previous week. The halftime show acts as an amplifier, introducing artists to new audiences while reigniting passion among existing fans. For performers, it’s less a gig and more a global relaunch.

The benefits extend far beyond music streams. Social media growth is another major payoff, and Bad Bunny is a clear example of how powerful the halftime spotlight can be. In the period surrounding his Grammy success and Super Bowl buildup, he gained more than 900,000 new Instagram followers, pushing his total beyond 50 million. That kind of growth translates directly into long-term value, from tour ticket sales to brand partnerships and cultural influence. To put things into perspective, brands pay extraordinary sums for far less exposure during the Super Bowl. According to NBCUniversal’s head of global advertising, Mike Marshall, a single 30-second commercial during the broadcast sold for around $8 million, with some companies paying more than $10 million for premium slots. Marketing experts often argue that even if a Super Bowl ad doesn’t lead to immediate sales, its long-term brand recognition is unmatched. The same principle applies to halftime performers: instead of paying millions for a fleeting ad, they receive around 13 minutes of uninterrupted global attention centered entirely on them.

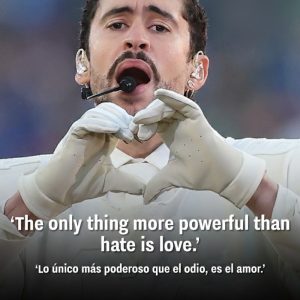

For Bad Bunny, the 2026 halftime show carried added weight beyond commercial benefits. His appearance came amid ongoing political controversy, particularly surrounding his outspoken criticism of former President Donald Trump and U.S. immigration policies. Over the years, Bad Bunny has repeatedly used his platform to advocate for Puerto Rico and immigrant communities, from wearing protest slogans during benefit concerts to releasing songs that directly criticize the federal response to Hurricane Maria. He also endorsed Kamala Harris during the 2024 election cycle and publicly condemned ICE raids, concerns that even influenced his decision to skip mainland U.S. dates on his world tour. Against that backdrop, his Super Bowl performance became more than entertainment—it was a statement. Singing entirely in Spanish on one of America’s biggest stages, Bad Bunny framed the halftime show as a celebration of culture, identity, and unity. For him, the value of the moment lay not in a paycheck, but in the opportunity to speak to millions on his own terms.

Ultimately, the reason Bad Bunny won’t be paid for his Super Bowl halftime show reflects the strange economics of modern spectacle. The NFL preserves a tradition that treats halftime performers as cultural ambassadors rather than hired acts, while artists accept the deal because the exposure can reshape their careers. In Bad Bunny’s case, the performance arrived at a peak moment: fresh off Grammy wins, amid intense public debate, and with a global fanbase ready to grow even larger. The NFL may not write him a cheque, but the ripple effects—from streaming spikes to sold-out tours and lasting cultural impact—are worth far more than a single night’s fee. In a media landscape where attention is the most valuable commodity, the Super Bowl halftime show remains one of the few stages where artists are willing to perform for free, knowing the spotlight itself is priceless.